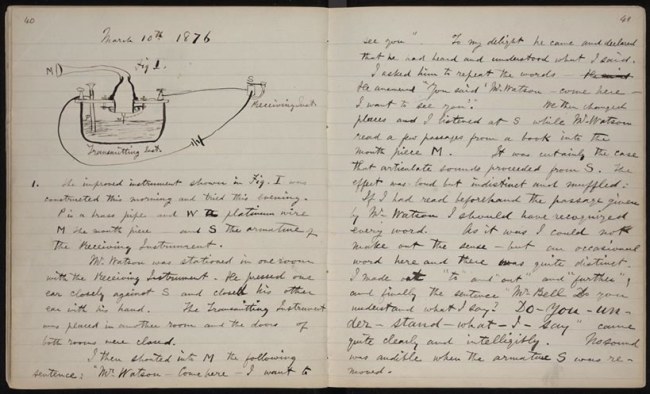

Bell’s diary entry for March 10th where he records the words he said to Watson (bottom of first page)

SOURCE: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trr002.html

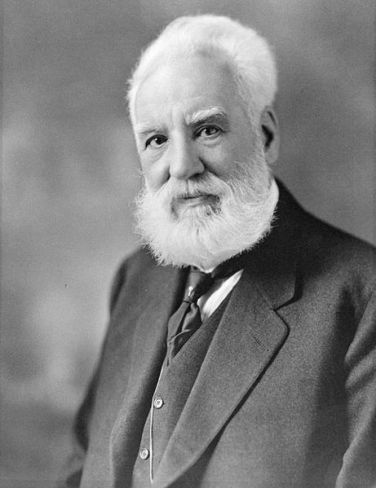

On this day in 1876 the first telephone conversation took place between Alexander Graham Bell and his lab assistant Thomas Watson. Bell had recently secured the patent for his new invention – the telephone – and three days later succeeded in making a call. He summoned Watson from the next room thus making the first, albeit very brief, telephone call. Controversy surrounds the invention of the telephone, as there have been claims that the credit for the invention in fact rests with another inventor: Elisha Gray. Gray had also been working on a device for transmitting voice messages and both filed the patent the same day, leading to speculations about who got there first.

We can endlessly debate who deserves the credit for the invention of the telephone. However, whether erroneously or not, it is Alexander Graham Bell whose name is synonymous with the invention. Without that first, fleeting, conversation between Bell and Watson, there may have never been any more. So next time you’re on the phone to a loved one, dealing with a call-centre, ordering takeaway or having a phone interview, remember those nine words Bell spoke on March 10th 1876.

“I then shouted into M [the mouthpiece] the following sentence: “Mr. Watson, come here — I want to see you.” To my delight he came and declared that he had heard and understood what I said”

– Bell’s diary entry from March 10th 1876